- Home

- Susanne Dietze

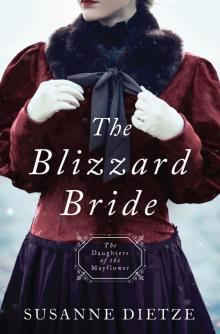

The Blizzard Bride Page 13

The Blizzard Bride Read online

Page 13

“Freezing means coat,” Hildie said.

“We have a treat today.” Abby hoped to distract Willodean from the oh-so-terrible prospect of wearing a coat. “Bartholomew is bringing apple cider for us to heat on the stove.”

“I wish it was cocoa.” Willodean tugged at the neck of her red sweater.

“Can I have cocoa?” Patty tilted her head to the side.

“Maybe we’ll make some tonight.” Hildie smiled at Abby for the first time in days. Perhaps her wounded heart was healing a little after their talk last night. “Abby, don’t forget to take the big cook pot with you for the cider. I put it by the front door for you. Now then, I was going to bake today, but since it’s not freezing, I think I’ll launder sheets instead. We’ll be getting out the tub, Patty.”

Patty clapped. “Can I give dowwy a bath?”

“Yes, when I’m finished with the sheets, you may bathe your doll.”

Abby glanced at Hildie’s protruding midsection. “Are you sure, Hildie? All that wringing and stretching’s sure to fatigue you. I can do it after school.”

“They’ll need all day to dry. Besides, the fresh air will do me good.”

Nevertheless, Abby stripped the sheets from everyone’s beds before she and Willodean left for school. Hildie kissed Willodean’s cheeks. “Wear that coat, you hear? And if you find mud puddles, don’t splash, please. Your shoes are so new and nice, I’d hate to have to scrub them already.”

“Yes, Mama.” Willodean rolled her eyes and hugged Bynum and Patty goodbye.

Abby took up the cook pot and her lunch pail. “Thanks for these. See you this afternoon.”

“Have a good day,” Bynum said. Hildie and Patty waved.

How could it not be a good day? The sky might not be blue, and if she wasn’t mistaken, a few snowflakes drifted onto Willodean’s shoulders, but they melted on contact. No matter the weather, though, Abby had a new heart this morning.

Lord, I’ll start the day with prayer. Thank You for each of my students. Please reveal their needs to me today and show me how to help them be all that You would have them be. I also ask for Your protection from Fletcher Pitch. Where is he, Lord? Protect Dash too. I’m so sorry I said those awful things to him, Lord …

Her prayer might be rambling, but she was pretty certain God didn’t mind. Mother had always said the conversation between friends was more important than the content. She’d meant that Abby could be silly with her friends, but the notion held some wisdom. It was good that folks talked, whether they were friends, or creature and Creator.

Maybe Mother’s tidbits came down through the family from her Mayflower ancestor.

“Say, Willodean, do you remember learning about the Mayflower from your last schoolmaster?”

“We didn’t learn about flowers, but I want to.”

Abby grinned. “It’s not a flower; it’s a ship. A special one. I think we should talk about it in class.” Eighth graders Coy, Josiah, Bartholomew, and Berthanne would be tested on American history before graduation, anyway, and she must be certain they were prepared.

Willodean sighed. “Can we learn about flowers too?”

“We may. What’s your favorite kind?”

“Daisies.”

“I like those too.”

It was hard not to think of flowers and spring today, with the temperature rising. It was such a lovely change that it was difficult to concentrate on anything once they arrived at school, especially once the aroma of apple cider filled the schoolhouse. At last Abby excused the children for noon recess. “When you come back in, we can enjoy our cider.”

Fortunately she’d had the foresight to request the children bring a tin mug to school. She downed her sardine sandwich quickly—it had never been one of her favorites—and used her remaining lunch break to pin twine along the north and south walls, above the windows, from which to display the children’s artwork. She hung the self-portraits they’d made—neither Micah nor Kyle said they resembled their deceased fathers, unfortunately—but there was still ample room on the twine for more artwork. After cider, she’d give her pupils some colored paper scraps to make flowers, and she would pin them to the twine too. The classroom would look like a garden, even though it was winter.

She picked up a stub of limestone chalk and wrote on the board beneath today’s date of January 12. Create a flower and enjoy cider. A delightful way to end the day.

She mixed glue paste and went outside. “Come inside now.” Abby waved at Burt Crabtree, who was working on his fence in his shirtsleeves. He too must be enjoying the unusual weather today.

Once inside, Abby moved to the stove. “Gather your cups, and I’ll ladle cider for you. Youngest to oldest, please. Yes, Willodean, that means you’re first. Get in line, thank you.” She scooped a steaming mugful for Willodean, then served Oneida and Jack. “While we drink, let’s do another art project. Glue pieces of scrap paper together to make flowers to decorate our wall.”

Coy’s groan was not unexpected. “I don’t like flowers.”

“You may make a tumbleweed if you prefer, Coy.”

He shrugged. “All right.”

She’d make a flower too. She settled at her desk and took a sip of the warm, sweet cider. “Delicious. Bartholomew, please thank your mother for me.”

“You’re most welcome, ma’am.” Bartholomew’s legs shifted after he spoke, drawing Abby’s gaze to the ground. Almos was seated in front of Bartholomew, his canvas sack at his feet. Nothing moved beneath the fabric this time, but it definitely bulged in a skunk-like shape.

“Almos?”

“Yes, ma’am?”

She glanced at the sack at his feet. Instantly, his shoulders wilted into a guilt-stricken frame.

“You brought Stripey back to school? Oh Almos.”

He scooped up the sack, cradling it like a baby. “I had to. He misses me.”

“That may be, but we cannot bring animals to school.” Stripey wriggled. “I shall have to speak to your parents, but I expect you to tell them why you’re home early today.”

“Now? You’re sending me home early?”

She glanced at her timepiece. “It’s not that early, but yes. I warned you what would happen if Stripey returned to school.”

Coy snickered. “Maybe if I get a skunk I can get sent home early too.”

“You and I would work out an arrangement for Saturday school.”

His jaw dropped in horror.

Almos loosened the sack. “Can he tell everyone goodbye?”

“May he, and oh dear, you’ve already pulled him out.” Abby’s stomach flopped. The creature nestled in Almos’s arms, blinking against the light, ears rotating. Almos lifted one little paw in a wave. She had to admit, Stripey was rather endearing.

The classroom erupted in coos, shrieks, and exclamations of rapture. But if Stripey were frightened or intimidated? Her classroom would reek for weeks. She nudged a few small pairs of shoulders back. “Return to your seats and finish your flowers. Almos, we’ll see you tomorrow.”

Almos gently lowered Stripey into the sack. “What about my flower?”

“You can finish tomorrow after the spelling test.”

Almos’s sister Berthanne, of course, had finished her red-and-pink blossom. The circular petals reminded Abby of a peony. “Yours will be the first I pin to the twine, Berthanne. You may be excused with Almos. I know your ma prefers you to walk together.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Abby escorted them into the vestibule but didn’t involve herself with their coat buttons as she usually did. She didn’t dare move her gaze from Stripey in his sack, and besides, it wasn’t that cold out. After waving goodbye, she fastened Berthanne’s peony to the twine, first of their spring garden. It was spring in her heart too.

Lord, thanks to You we have this wonderful day in the midst of winter. After school I’ll go to the inn to speak to Dash. Please give me words to say so he’ll see how sorry I am.

She was humming when she

sat down to finish her own flower, a vibrant yellow daisy. She didn’t realize until she got to the chorus that it was that melody Dash used to whistle.

Dash whistled as he left the inn for his lunch respite. His growling stomach was louder than the tune, but little wonder, since it was what, two o’clock? Hours since he’d had his breakfast of corn cakes and bacon. Lunch was late today, thanks to that guest Unger’s request that Dash clean and polish his carriage before he checked out.

Unger clearly wasn’t Fletcher Pitch. No one in Wells was, to the best of Dash’s knowledge. So where was Pitch? Dash’s informant in Kansas City was certain Pitch was en route to Wells to get his son. He’d said the name of the town and said he should’ve guessed his boy was here, once he saw the name on a map. Whatever that meant.

So where was he? Waylaid, or was he biding his time, hiding on an outlying farm somewhere?

Dash didn’t know anything for sure when it came to Pitch—or much of anything else, either, except he and Isaac were out of coffee, which was why he headed to the general store before he grabbed a bite to eat.

He also knew his scarf was much heavier than the day required. What odd weather. Yesterday he’d slipped on the shell of ice coating the walk, and today his footsteps punched through.

One other fact he knew: he was miserable.

He’d brought his misery on himself, though. He’d allowed his temper to get the better of him when he told Abby he didn’t like who she’d become.

It wasn’t even true. Well, he didn’t like some of her choices, like leaving her Bible behind, but that didn’t mean he didn’t care for her. He always had and always would, and he shouldn’t have said such things. Especially that she didn’t accept him for who he was back then.

She had accepted him, to the best of her ability. She probably didn’t understand the ways she didn’t accept him, but her father had been right. She wouldn’t have been happy, had he stayed in Chicago. He believed it to his core.

He’d been hurt at her calling him viperous and deceitful and that other word he couldn’t even remember now, but he understood why she lashed out. He’d embarrassed her when he stopped the dance, but he assumed she’d take him to task for twirling her around like he had. What a foolish thing that had been, but she’d been so sweet, laughing like she had years ago.

He’d have to apologize, and do it right this time. Tell her the truth, or at least a version that wouldn’t cause undue pain. Not that he wanted to have that discussion right this minute. Seeing her last night had sliced through him with greater efficiency than a skinning knife. But maybe in a day or two …

He’d worry about it in a day or two.

Lord, I said things I shouldn’t have. But oh, this is harder than I want it to be.

Dash had asked Jesus to be his Lord when he was ten or thereabouts, before his mother died but after he’d met Abby. Seventeen years ago? A long time in some ways. He still had plenty of questions, and lacked confidence in his faith. He sought the approval of others more than he ought to. He didn’t love the Lord more than himself, if he was honest. He wanted to, but did he really?

Maybe for five minutes. Then he put himself first again—he had things to prove, after all. To his father. To Abby’s father. To Abby—or the shadow of her, anyway. Each time he achieved something, a thought burned in his brain, quick as lightning. If only they could see me now.

He’d spent the past six years working to be a man worthy of Abby in her father’s eyes, even though Mr. Bracey would never have been pleased by Dash’s job for the Secret Service. But Dash was starting to come to the understanding that he should be striving to be his best self, not to impress Abby’s father or to prove something to the world.

He should be striving for the Lord and let the Lord sort it all out.

Thanks for the reminder, Lord. Now please help me to live it.

The bell over the door of the general store chimed at his entrance. Mr. Knapp, the proprietor, looked up from helping his sole customer, a gray-haired woman Dash recognized from the handkerchief dance at the mayor’s birthday party.

“Hello.” His shoes made damp thumps on the floor as he approached the counter.

The woman gave Dash a sly smile. “Hello, again. You tried to catch my handkerchief at the party.”

“I did.”

“I’d have let you, if I hadn’t been instructed otherwise.” Mercy, did her lashes flutter? “Won’t you introduce us, Mr. Knapp?”

He stroked his neat mustache. “Mrs. Leary, meet Mr. Lassiter, the new hostler at the inn.”

“How do you do?” She offered her hand.

After the exchange of pleasantries, Mrs. Leary tutted. “So you’re the one who came to Wells for our new schoolmarm.”

He forced a laugh. “Alas, schoolteachers must remain unwed.”

“Perhaps that’s why I never taught school.” She cackled. “I’m a seamstress.”

“You must employ Mrs. Story.” At her arched brow, he grinned. “I live with Isaac Flowers.”

“Ah, yes. They’re becoming friends, aren’t they? Mrs. Story isn’t just my employee, you see. She and little Micah live in my spare rooms.”

Mr. Knapp cleared his throat. “Speaking of your work, Mrs. Leary, did you care to finish selecting the notions for your order?”

She sighed and returned to the catalog on the counter between them. “These and these.”

“I shall put in for them. Anything else?”

“Not today. I must see to a few more errands and return to work. Nice to meet you, Mr. Lassiter.”

He tipped his hat. “And you, Mrs. Leary.”

Once he’d received his coffee from Mr. Knapp, Dash paid with a twenty-dollar bill, a far larger denomination than was necessary, but it ensured he’d receive several smaller bills in change in his never-ending quest to locate counterfeit currency. Since no one was in the store, he took his time, feeling the bills.

Mr. Knapp leaned over. “I didn’t count right?”

“No, you did.” Dash placed the bills in his wallet, two of which varied from the others in thickness. They were Pitch’s. So, Pitch wasn’t here but more of his bogus currency was. Coincidence, or had someone brought them here intentionally? “You ever have a problem with counterfeit money here in Wells, Knapp?”

“Once. Customer left a dollar on the counter and Oneida spilled her lemonade on it. I’d told her not to drink it in the store, but good thing she did, because it made the ink run.”

Dash had seen that approach to counterfeiting a few times. The process was painstaking for the counterfeiter, requiring long hours copying a genuine bill. As long as the bill didn’t get wet, it could pass muster. Pitch’s work, however, didn’t suffer the same weakness. His inks were of the highest quality.

Knapp shrugged. “I’m sure it was left by someone passing through. Wells isn’t that type of town.”

“I hope that’s always the case.” Tin of coffee in hand, Dash nodded farewell and ventured into the street. He nodded at Mrs. Leary, who’d paused several feet away to fiddle with her gloves, and started toward home and his plate of bacon.

The air was still, heavy, with that strange silence that happened in the summer when the bugs and frogs ceased their chirps and croaks for no discernable reason. Like something was about to occur. Odd. His next breath was tinged with cold and the peculiar smell of air before a lightning strike.

A roar thundered behind Dash, so loud and intense that his first thought was a train derailed. But the train hasn’t come to Wells yet. The noise wasn’t just in his ears, though. It was in his body, vibrating. He turned to look for the source of the clamor.

Dear God. The northwest sky was alive with a rolling black cloud, tumbling over itself toward town. Heart filling his throat, Dash rushed toward Mrs. Leary. He hadn’t taken two steps when a violent blast of frigid wind hit them, knocking him sideways and stealing his hat. Mrs. Leary bent forward. No, she was bent, forced from behind, her head shoved almost to her knees. She pulled

herself upright and it looked like she cried out, but any noise was carried away by a second gust, more powerful than the last. Far colder too.

Pain like a thousand needles pricked his face, hands, ears, the part of his neck not covered by his scarf. Shattered glass?

Ice crystals. Dash knew it the moment he saw what looked like flour caking Mrs. Leary’s shoulders and hair.

He grabbed her arm, but she tugged away.

“No!” Could she hear his shout? “We must get to safety!”

Her mouth worked, but he couldn’t make out her words. But then he understood. Her bonnet had gone the way of his hat and she wanted it back.

The snow and wind seemed to be coming at them sideways, and the sting was unbearable. They couldn’t retrieve hats or anything else, not now. But she pulled from his grasp, her gaze on the ground.

There was nothing for it. He scooped her into his arms.

The storm followed them inside the general store and sent papers flying in swirls of cold. Someone shut the door behind them—Mr. Knapp, speaking, but Dash still couldn’t hear. His ears buzzed.

Dash lowered Mrs. Leary into a chair near the stove and then dropped to the ground at her feet. He was vaguely aware of Mr. Knapp covering his shoulders with a blanket.

“What’s happened?” Mrs. Leary’s tremulous voice was the first bit of conversation he comprehended.

Mr. Knapp went to the window. “Never seen a storm come on that fast.”

Dash cleared his head with a shake. What time was it? Close to two, wasn’t it?

If it was after two, then school was out for the day.

Abby.

Dash shoved the blanket from his shoulders and ran for the door.

CHAPTER 11

At first, Abby thought one of the children scraped a desk across the rough floor. Then she realized the noise was far too loud and persistent, like a trackless train sped toward the schoolhouse. The children rushed to the north windows.

A wall of dark cloud seemed to touch the ground. Before she could react, wind slapped the schoolhouse, shaking the door and windows and smacking them with hail—no, it was snow, loud as bullets but fine as powder, sneaking beneath the panes. And with it came cold.

A Future for His Twins

A Future for His Twins The Blizzard Bride

The Blizzard Bride A Mother For His Family

A Mother For His Family My Heart Belongs in Ruby City, Idaho

My Heart Belongs in Ruby City, Idaho The Reluctant Guardian

The Reluctant Guardian